Teaching an Old Puppet New Tricks

On "Puppet Origin Stories@ONE-TWO-SIX" (2022) by The Finger Players (Singapore)

Puppet Origin Stories@ONE-TWO-SIX by The Finger Player is not just about the history of puppets. There are also alternative realities and thrilling new reimaginations.

This programme is a creative response to the “Puppet Origin Stories” repository of TFP puppets used in previous productions that has been consolidated by co-Artistic Directors Ellison Tan and Myra Loke. It is slated to become an annual event for the company to celebrate their trove of beloved puppets.

In fact, Cairnhill Arts Centre, the venue of the show and home to several arts groups including TFP, is a focal point as well. The audience is introduced to the site, and given a brief history of its transformation and existential precarity before the evening even begins.

The site is peppered with exhibitions of TFP puppets (some with Toyogo Boxes) from the repository. The installations are accompanied by invitations to audiences to respond to the puppets in their own way by taking photos and writing captions.

Then, front-of-house tour guides lead us to the main event: a triple-bill of performances by Becca D’ Bus, Tan Wei Ting and Hairi Cromo—a drag queen, a filmmaker and a movement artist respectively.

In SUCK SWEAT DRY, BABY! by Becca D'Bus, the TFP rehearsal studio is transformed by pink and blue hues into a discotheque both out-of-place and time. The work, performed by Becca D’Bus, Deonn Yang and Mitchell Fang, is full of contradictions, apt for a queer commentary. Each scene a spectacle painted on layer by layer, the play between forms and contexts twists and undercuts audience expectations fun ways.

For one, the drag queen-puppeteers far outshine the plain-looking puppets (Samsui #7, Moon Baby and Sponge Girl), already decoupling puppet from puppeteer and challenging notions of essentialist oneness and tradition. In one scene, drag queen Mitchell Fang and Moon Baby huff and blow at an imaginary coffee in the orange glow of a stage-light sun, atop a mountainous queer body (Becca). It is a scene enjoyable and unforgettable; its peaceful and gentle mundaneness so sincere against the absurd constructed-ness of the moment.

Another fan-favourite, judging from the audience’s guffaws: Sponge Girl and Samsui #7 meet at a bar, and they get it on. Any sense of decorum associated with these puppets as an innocent girl and a sacred 'Singapore History Archetype are thrown to the wind. The deadpan drag-puppeteers make wet, sloppy sexual sounds, complete with quirky use of headlamps to light the scene with intimacy and a sense of voyeurism.

Inter-splicing these scenes are vignettes of Becca lip-syncing to Ring of Fire, a queer wedding, and two pride flag-headed cyclops making out intensely. Kudos to lighting designer, Genevieve Peck, for tying the disparate scenes together with bright colours and deep shadows that intensify the feeling of wonderland and queer dreaming. There is a lot to capture in this work; strong images that bounce off me with no clear instructions, but leaving blunt and indelible impressions.

The piece ends with the performers introducing the histories and transformations of the props and puppets used; objects that have been made irreverent, some would say, by SUCK SWEAT DRY, BABY!’s treatment. Yet I leave the experience thinking about how this adds another layer to their fabric flesh. You can, indeed, teach an old puppet new tricks, and I am thrilled that the puppets are allowed to play beyond the confines of their Toyogo—and our own—boxes.

The second item, Ah Ma, is the emotional heart of the three.

Right off the bat, it strikes us with a sense of nostalgia, with a video of TFP’s well-known touring productions, A.i.D (Angels in Disguise) playing in the background. In the video, a younger Tan Beng Tian, one of TFP’s co-founders, puppeteers Ah Ma, who has dementia. Ah Ma’s dementia is represented by a magnetic jewel that drops out when she falls, leaving a gaping hole in her head.

In the present moment, Beng Tian herself puppeteers the same Ah Ma puppet in sync. This layering of the past against the present is evocative—the Ah Ma puppet looks exactly the same, but I feel the weight and graveness of time past.

She explains that TFP first started as part of The Theatre Practice’s Children’s Wing. However, due to financial sustainability issues, the children’s wing had to be cut. TFP then established itself as a separate entity and grew to what it is today.

Ah Ma presents an alternative future to this past. Suppose TFP was never reborn and had to fold once and for all? In this story, Beng Tian donates the Ah Ma puppet to the ‘Singapore Art History Permanent Exhibit’ in a fictional museum, where Yazid Jalil plays both a curator and a lowly security guard. When Ah Ma awakens, she is lost and lonely, in a cold and sterile glass display case instead of her familiar Toyogo box. She calls out for Beng Tian, her beloved puppeteer, to come to her rescue.

The work raises questions of what it means to preserve our memories. Is culture meant to be free or live inside of a glass case? Is art meant to be practised and passed on rather than stamped out and left forgotten on a pedestal? What does it mean to honour our histories, our memories and our loved ones? Against this backdrop, perhaps Ah Ma's magnetic jewel, which represents dementia in the story, is also symbolic of a cultural amnesia.

This piece is an odd one: a staccato public service announcement, ticklish comedy sketch and heart-wrenching drama all rolled into one. It is not a piece that policy makers or museum workers will love, with the curator being the unempathetic, single-minded figure of oppression and surveillance. But Beng Tian’s earnestness in playing herself and an endearing Ah Ma gives the work the big dose of sincerity it needs. As puppeteers, Yazid and Beng Tian are deft and subtle in keeping Ah Ma terrified, confused, but determined—altogether a heartbreaking thing to watch.

The result is wholly genuine, with an ominous plausible reality looming in the background, and makes the best of us emotional with the thought of losing TFP, and these puppets who have names, histories and significance.

All these remind me of my own early encounters with TFP. I was 16 and part of a puppetry workshop. I even scored a photograph with the TFP team, including Beng Tian. Strikingly, she is wearing the same beige tunic from A.i.D. in the photo.

After watching Ah Ma, I think about how different life would have been had there not been a TFP for me back then. How devastating if I and countless others before and after me, never had the chance to encounter such arts in all its living, breathing richness? In that respect, Ah Ma is not just an urgent call to action, but a reminder that we are the sum of our histories and cultural memories. What are we without them? I would hate to think of the answer.

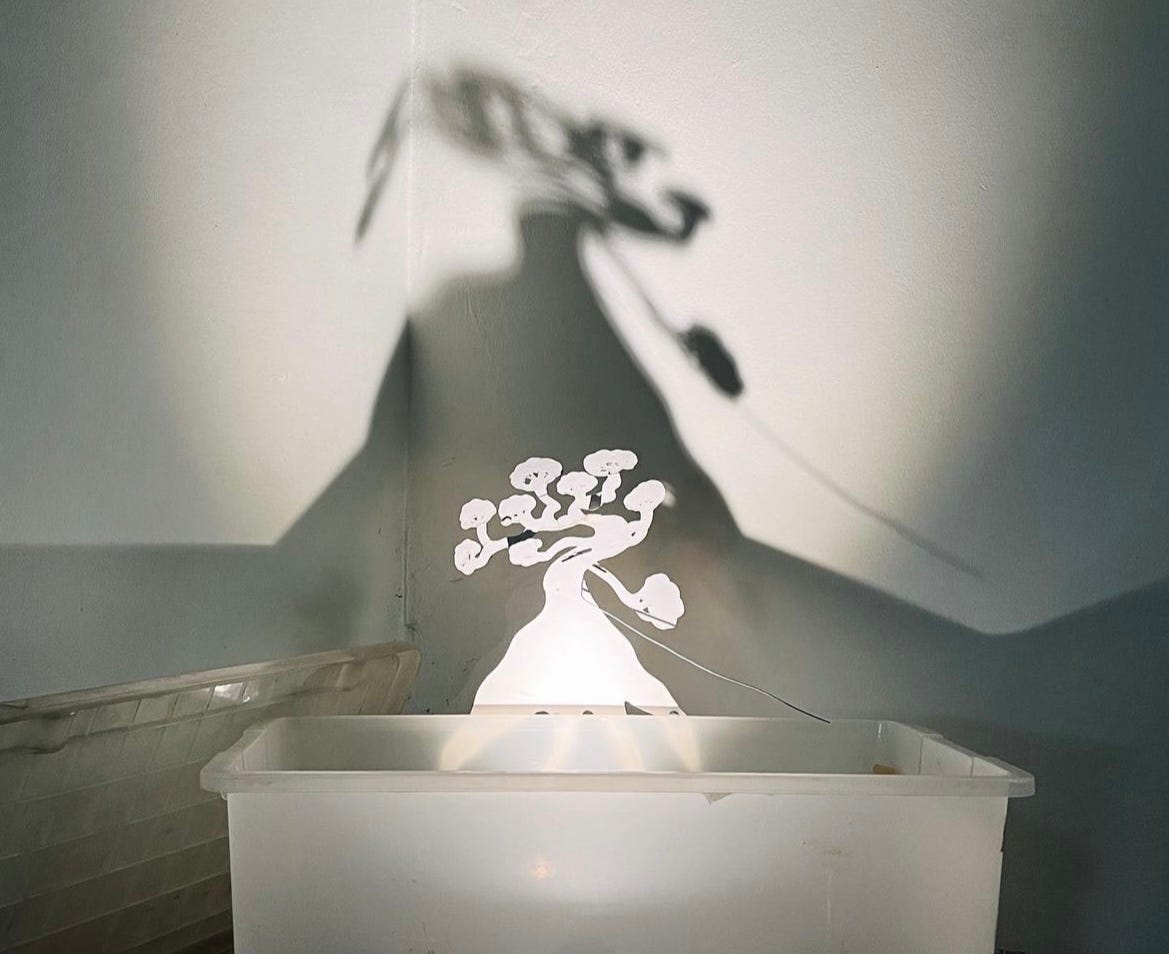

To round off the evening, Jabber by Hairi Cromo, follows the story of Pol, a primary school boy, learning to deal with confusing negative feelings after misbehaving in school. His inner struggles manifest as Shadow, an amorphous being that haunts him.

Pol is the Peng puppet, puppeteered by Liew Jia Yi, while Shadow is the Faceless Maiden puppet donned by Chai Jean Yinn.

While simple and effective, the story felt a little long. However, with the detailed puppeteering work done by Jia Yi and Jean Yinn’s strong movements, one is unable to look away.

I loved watching Pol with his slouchy big head; his rattly metal limbs swimming and jabbing exactly like an eager and curious child, restless and yet relentless. Liew’s pouty voice-acting and details makes Pol adorable.

In contrast, the faceless Shadow has a mysterious and all-consuming presence. Jean Yinn becomes disproportionately taller when wearing the puppet atop her head, her body hidden by layers of scarves that make Shadow wider and more flitting. Jean Yinn’s calculated leaps and flourishes across the space are impressively sustained throughout. With the simple story and uncanny characters, Jabber is both familiar and foreign, an overall unsettling experience.

By the end of the evening, I have gained a new-found appreciation for the puppets: how they move, what they represent and most importantly, how they can be transformed. In fact, my companions for the evening, community and social workers, ruminated on the parallels of Ah Ma and Jabber to ideas of autonomy and control within the palliative care and mental health realm. Their encounters with puppets have been few and far between, but the experience undeniably opened their eyes to new ways of interpreting the world they know.

Puppets can do that; they teach us to see ourselves through fresh lenses and what it means to relate to each other—all through the humble object and our own imaginations. I walk away from Puppet Origin Stories@ONE-TWO-SIX with more than just histories, but also a new found relationship with the beloved TFP puppets and a sense of protectiveness over them.

Activating the puppet repository—and preserving the art of puppetry—is so critical. Whether or not they are challenging traditions, proposing an alternative reality or telling timeless tales of self-discovery, puppets are beloved parts of our arts and human histories. Above all, these puppets teach us to live in the present and to envision a future, so that we can continue to tell stories that matter to all of us.

Support The Finger Players’ on their quest to tell puppet stories!

+++